At barely 16, I read a book that made it easier for me to put a name onto some of my teenage anguish: bullshit. As a reward that I passed a second high school test, which gave me two more years of high school and a chance to take a college entrance exam, my step father took me for two weeks to a resort on the Black Sea Coast, as guests of a family of his friends. For me, then, that was the equivalent of spending two weeks in Hawaii in a five-star hotel.

During the day we would go to the beach and stay there until early evening, when we would return to have dinner with the hosts, and make small talk or even go for an evening stroll.

My memories from that time are about my daily struggle with a rather large volume of non-fiction and my first evening in a real disco. The book was Karl Marx’s Capital, Vol. 1.

Capital, Vol. 1.

The disco evening remained bland by comparison.

Every morning we took the bus from the apartment building to the beach and I would carry that book with the blanket and start reading as soon as I would lie down on my tummy bathing in the beautiful sun of those days. The reading would not last many minutes, because sometimes after a single paragraph I would ask my father to vet my understanding. I cannot recollect our moments on the beach, but I would not be too far off imagining that I would briefly lay on my tummy, read something, and then indignantly I would sit up and ask him whether I was correct saying bullshit, bullshit, bullshit – my 1983 Romanian experience was as far removed from a Marxist society as anybody’s 1945 Romania.

Is it me or do you think it too, dad, that only the master and some of its few minions had changed since it all began?

I loved that summer. I grew up much more than I expected partly because I gave myself permission to continue learning and living and living and learning, and partly because girls grow fast when they reach 16. And I did. I started those very days by noting that the Romanian version of The Capital was a translation of an English translation. That is how I learned to compare different versions of the same text and notice differences of nuance. I also learned to use my photographic memory and distinguish myself months later at the regional Olympiads in political economics, where my answers would be peppered with Marxist quotes…in English.

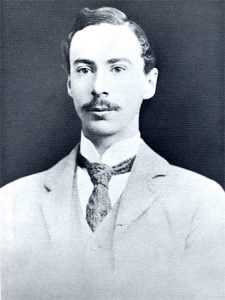

Nothing challenged my belief that the Romanian socialist society had very little in common with Marxist socialism, but I was never able to articulate it in a crisp manner. That is until I came across The Basic Writings of Bertrand Russell.

Russell explained like no one else where soviet socialism failed: although the state became the ultimate property owner, and leveled the economic power among citizens, the state did not encourage democracy and thus equal political power among citizens, but monopoly of power, which desiccated the system and eventually annihilated it because the people with economic power eventually had to match their political thirst with economic power, as well. Russell understood better than no one that the enemy is the monopolist, whether in Soviet Russia or Capitalist America. Even more interesting, Russell was a visionary in terms of the current digital economy built by unpaid workers who do it because it satisfies their artistic sensibility and their capitalist entrepreneurial dignity.

Russell explained like no one else where soviet socialism failed: although the state became the ultimate property owner, and leveled the economic power among citizens, the state did not encourage democracy and thus equal political power among citizens, but monopoly of power, which desiccated the system and eventually annihilated it because the people with economic power eventually had to match their political thirst with economic power, as well. Russell understood better than no one that the enemy is the monopolist, whether in Soviet Russia or Capitalist America. Even more interesting, Russell was a visionary in terms of the current digital economy built by unpaid workers who do it because it satisfies their artistic sensibility and their capitalist entrepreneurial dignity.

The Internet seems to have solved the main handicap of any capitalist society: the class warfare, because we are all consumers and producers and the capitalist is so ethereally removed that we forget who makes the buck as long as we feel creative, productive, and consequently happy. Here are Russell’s amazing predictions even for someone as nearsighted as myself:

The evils of the present system result from the separation between the several interests of consumer, producer, and capitalist. No one of these three has the same interests as the community or as either of the other two. […] It is surprising that, while men and women have struggled to achieve political democracy, so little has been done to introduce democracy in industry. I believe incalculable benefits might result from industrial democracy […]

Russell, 1916.