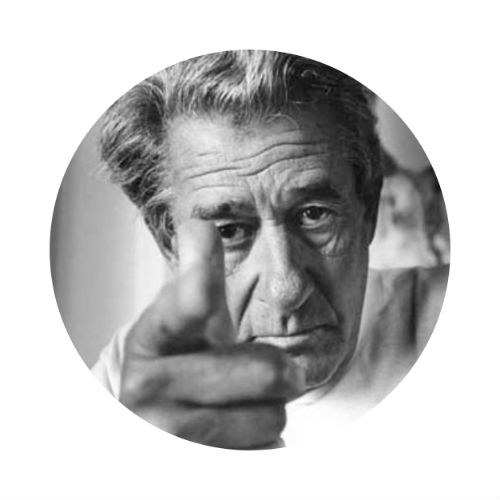

Sometime during the unsatisfying intercourse between 1990 and 1991 I went to London and I desperately cried in front of what I only thought to be a mere theater. I could not afford the meek amount of less than 6 pounds to buy two student tickets to see Mr. O’Toole, in what was described as a show where the main character suffers tremendously to the pure delight of the audience. Here is a clip from that performance and a subsequent interview.

That performance was repeated. The Times obituary describes it:

And in the theater his emotional depth was apparent when he played the alcoholic journalist and gambler Jeffrey Bernard. The third and last time he took the role, many felt an essentially comic performance had darkened, deepened and grown in pathos. It was as if Mr. O’Toole were meditating on past loss and waste — as if he were offering a rueful elegy to himself.

Perhaps. Does it matter? I doubt it. What it matters is that in my last teen years I chose to spend my little money and very limited free time waiting on lines to see Lawrence of Arabia (who can ever forget the last scene?), Goodbye Mr. Chips, How to Steal a Million, and Becket. The latter multiple times. There were a few public theaters where you could see those movies: at the equivalent of Film Forum, and the Student Club, and in some attic at the University. They were programmed well in advance, and sometimes a movie critique would introduce them to the young cinephiles. These were the last years of the 1980’s, when bleakness was promoted as a means to break down the youth of Bucharest.

Everybody around me adored Peter O’Toole. I cannot remember any Richard Burton fan during my viewing of Becket, though we all knew his work and life dallies very well. I have always wondered why this admiration for the difficult Irish thespian. I will venture a guess: Peter O’Toole brought grimness to his roles and made fun of anybody who could not face their lives’ vicissitudes. Life is to be lived and damn those who forget that!

Good job and Goodbye Mr. O’Toole!